|

George Eastman Hall

upcoming

exhibition

Molnár Zoltán

Brazil Diary 2008

Opening remarks by Boldizsár, Kõ artist

with the participation of Capoeira Senzala

Curator: Gabriella Csizek

Open to the public:

13th May to 26th June 2011

Every weekdays: 14.00 - 19.00

Weekend: 11.00 - 19.00

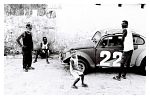

Brazil Diary

In 2008 I had the opportunity to get acquainted with ethnic groups living in

various regions of Brazil, their everyday lives, traditions and celebrations.

The many peoples living there made an enormous impression on me. The diverse

nature of various ancient cultures, the pomp of the colonizers and the

traditions of immigrants have lived on together. The aim of my photo series was

to bring into focus one of South America’s living cultures, the lives of the

members of village communi?ties who are in direct contact with water and depend

on the vagaries of nature for their livelihood. I made notes on chil?dren and

their environment in the slums or so-called favelas built on Rio’s steep

hillsides, in the huts standing on stilts in Belém and in the favelas of tin

shacks cobbled together on the outskirts of Salvador. The writing of my Brazil

diary and attending to the pictures gave them new meaning beyond the limits of

memory. I needed to look into myself in order to make progress and to arrive at

the next destination I had set myself.

I left my water thermometer at home; I will ask a local photographer where I

can get one in Salvador. Today I had soya for lunch, beautifully prepared and

served by Marcia and tuna ?tute at the weekend is the doorman, so we have to

look after ourselves. The first weekend I was the terror in the kitchen. I used

aubergine too and made ‘letcho’ with potatoes and ?toes and the rice pure white.

I decorated the potatoes with parsley. Red, white and green. It was Hungarian

territory. ?ing two little babies on its back. They are the size of squirrels

with long thin tails, grey fur, their ears are like a whitewashing brush

standing on its head…

Salvador, 28.10 2008

Zoltán Molnár

An iguana lives in the compost pit. Beautiful blue-green colours mingle on

its skin. Something new for me. I have seen such creatures in the zoo or in pet

shops; here it climbs up the fence or picks out an eggshell in the rubbish. I

found out today that football is called ‘fuchiballi’, but have no idea how to

spell it. In the Earth’s southern hemisphere, even the water goes down the drain

in a different way. Centrifugal force goes in the opposite direction, from left

to right. While at home before the ?cies and means of subsistence, here it is

sugar and coffee. The sweet and the salty, black and white, north and south… …It

is difficult to get permission to photograph people. I would like to take

pictures of Black Brazilians. A quick scout round in the Institute library.

Good, varied sources, which are my bread and butter now. I found a great Pierre

Verger photo album. The blend still evident in Brazilian culture is held

together by the use of the Portuguese language. Amerigo Vespucci was the first

to set foot in Salvador in the Baia es Todos os Santos in the mid-XVIth century.

Salvador has a population of 2.5 million and the vast majority have among their

ancestors the slaves captured in Africa. Slavery was only abolished in 1889, but

the centuries of misery have left their traces and people still feel ?cient

African myths and rituals, which gave them the strength to survive even in

difficult times. The most important surviving elements of the culture of

resistance are Capoiera (a kind of acrobatic battle dance), the Carnival and the

Candomble (a religious cult). The dancers must not hit each other, though they

are performing battle rituals. They practice everywhere ?ment consisting of a

stick with a taut metal string in the middle and half a coconut at its base,

which increases the volume. I photographed the leader of the village Capoiera

community in a bicycle workshop…

Salvador, 29.10 2008

Zoltán Molnár

We made a little music yesterday. I played the berimbau. There are 10

beautiful villages on the island, each one different. There is a fishing

village, Baiacua, with only a dirt road leading to it. There is no regular bus

service. You have to squeeze into cast-off VW mini-buses. I wonder how many have

experienced these mini-bus transfers. The Argentinean boy drives. From the ferry

to the village, 21 people travelled on the mini-bus. There are motor bicycle

taxis, a bit cheaper than normal taxis, but more dangerous. There is a church

next to Baiacu village. It was built in the XVIth century. Only the walls are

left standing in the middle of the forest on a hilltop. A tree has grown in the

chancel, the roots creeping up the walls and the foliage taking the place of the

roof-timbers. When I stepped into the church, something flew away above me. At

first I thought it was a bat. I was wrong. I was aware of the loud flapping of

wings of a colibri. In Portuguese they are called ‘beija flor’ or

flower-suckers. Its feathers were red and blue. It hovered by the church wall

and tried to suck the nectar from a flower with its long beak. It was smaller

than a butterfly. I am going to a Candoble this evening, a religious service of

the Black Brazilians living here. It goes on until morning. The venue is kept

secret until the last minute. Taking photographs is forbidden, as it disturbs

the meditation and the concentration of collective energy…

Salvador, 02. 11 2008

Zoltán Molnár

...Candomble is behind us now. We arrived for the ceremony after nine in the

evening. One of the ‘Yankee writers’ and I went to the neighbouring village of

Amoreira. After much asking for directions and stumbling around in the dark, we

found the magical location, but there was not a soul to be seen. We thought the

event had been cancelled. After much ado we found a local member who set us

straight. It turned out we had arrived too early. We introduced ourselves to one

of the organizers, told him who we were and where we’d come from. He led us to

the location and told us about Candomble. Of course I didn’t understand a word

of his explanation of Portuguese religious history, but I did understand what

was permitted and what was not… Going to the WC is allowed, but leaving the

ceremony is forbidden. Taking pictures and filming is also forbidden. There is a

large enclosed space without windows divided by a wooden railing separating the

women from the men. The mysterious African religious service lasts until dawn –

this alarmed me at first, but they assured me there would be a break. Opposite

the entrance, there was a huge painting of the good and evil deities that would

be conjured up live. In front of the wall are royal thrones, chairs and drums.

Slowly the room filled up. The women wore white skirts, white blouses and white

scarves on their heads. The men, like the women, were dressed in white from head

to toe. They wore little hats like sailor’s hats. Everyone had a necklace worn

across the shoulders. The men greeted one another with a kiss on the hand. The

women, already in feverish preparation, sang and greeted the musicians before

the event began. Six women and a small child formed a circle and danced in front

of the thrones to singing, clapping and the rhythm of beating drums. Sometimes

they stopped to touch the ground, then their foreheads. This went on for about

an hour. The only air came through the door. There was a strange noise coming

from outside. Doors slamming. Quiet. The deity of good arrived in a beautiful

velvet robe. An amorphous form with no discernable body parts - no hands, no

feet, no face. Everything is one – in a splendid wine-coloured robe with various

mirrors sewn onto it. Two men beat the ground with switches around the god.

Drumming, singing and clapping again. Anyone who had not felt like clapping

earlier, was now beating the rhythm with their feet. The door slammed for good.

No one was allowed to leave. Then a conversation ensued between the ceremony

leader, the spiritual intermediary and the miraculous being that had arrived. It

consisted of a kind of murmuring and strange intonations without words and

sentences. Then drumming again and it went on like this until midnight. After a

small break, the deity of evil came amongst us, getting very close to the

participants. This meant the men’s section was pressed up against the wall in

fear that the otherworldly being would grab them. Shoving, shouting and

screaming from the women’s section too. The crowd was in a strange

transcendental state and I completely lost my sense of space and time. Then this

was repeated again and again – an ongoing battle between Good and Evil. After

the second break, at about two in the morning, they opened the door and escorted

everyone out, so they wouldn’t be seized by the spirits on the way home. We

arrived back at the Institute completely exhausted. I took the cloves of garlic

out of my pockets. I had taken them with me to keep the witches away. Breathing

together, drumming together with a Black Brazilian community is a good

feeling...

Salvador, 04. 11 2008

Zoltán Molnár

Yesterday one of the neighbours next to the Institute invited us to his

house. A Gypsy artist from Provence in Southern France. His garden is full of

sculptures. The Mona Lisa poster had found its way to the WC, there was a price

tag on it that read: 1.30 real. He was a real character. He had found two whale

backbones on the seashore. His name is Szergej Magyar. He does not speak

Hungarian, but he speaks Portuguese, French and English. We watched the results

of the American elections with him. People are very happy about Obama’s victory

here. I am unable to develop my films because of the heat. I must solve this

because of the exhibition reporting on my trip. There is a lab in Salvador and I

would like to take my negatives there. It costs 12 reals to develop a roll of

film. I will give them what is needed for the final submission. I am marking

each roll of film...

Salvador, 05. 11 2008

Zoltán Molnár

Still in Ilha de Itaparica in Bahia County. After lengthy negotiations, a

taxi driver finally agreed to take me to a fishing village that can only be

reached by a dirt road. I got to Baiacu at about ten in the morning. The

fishermen were getting ready for the next day’s fishing. Preparing sails,

repairing nets, putting palm leaves in the boat to protect the fish from the

sun. The village is isolated. People here live closed-off from the outside

world. After getting acquainted with the fishermen, I set out looking for

somewhere to stay. Adobe houses one on top of the other. A woman invited me into

one of them. They live in two rooms with nine children. It is a very poor

village. For them water means life. They live on whatever nature and Yimange

gives the fishermen. I tried to buy some fruit in the shop. The owner advised me

not to buy the bananas. Oranges were the only other choice. This time he

selected and even peeled them for me. I found a nice pub. There were black and

white pictures hanging on the wall. I asked the publican, who spoke English, to

help me find a place to stay and give me directions in the village. After a

while he offered me the couch in a room behind the pub. He listens to a lot of

music: rock, jazz, pop, everything. The next morning at seven, the women with

their buckets were already waiting for the fishermen and their daily catch. The

larger fish are cleaned on the beach. The smaller ones are put out in the sun to

dry. They salt them, put them in crates and then they are ready to go to the

shop. Their boats are cut from a big tree, much like we make our wooden tubs,

but the boats are much longer. I made friends with the oldest wood carver in the

village who makes the wooden boats. He showed me his workshop. On the way home,

I said good-bye to the fishermen, who had a good laugh at my muddy shorts.

Without a boat, one can sink up to one’s knees in the mud. Everyone has a boat

and a horse -which they use to get around the forest and which are easier to

maintain than a car or motorcycle. Baiacu is an oasis in an ocean of globalized

waters, at least until the road, already started, is completed...

Salvador, 09. 11 2008

Zoltán Molnár

I found a beautiful night moth. A silk moth I think. Its body and wings

looked as if it were still alive. We get hot water with the help of solar

panels. The whole village, even the policemen, carry drinking water from a well.

I was in Salvador yesterday. I found a lab where they develop black and white

film by hand. I will pick up the negatives on Tuesday next week. I am a bit

worried and hope they develop them well. I went by motorcycle taxi, wearing a

helmet, to a factory in Mucambo, the neighbouring village. The driver whistled

to the gateman, someone peeped out of a tiny window. After a short conversation

in rapid Portuguese, they opened the iron gate. There had been a

misunderstanding: I had information about the Cheramic Company that operates

here on the island and had expected to see pottery kilns and vases being

painted. Instead I got a brief look at a brick factory at work. This meant two

shifts from 9am to 6pm. In the end, when my shoulder was about to break off, I

finally put my bag down. Naturally it fell to the ground causing a minor camera

accident. The viewfinder and lens hood of my medium format camera were dented.

Luckily there is a workshop at the Institute and I was able to repair it and use

it again. At the factory, with the help of water and a machine, they are able to

press the reddish-brown Brazilian earth together. It comes out of the machine

much like a sausage early on the morning of a pig killing. They slice it with

wire and then the steaming bricks are taken to the warehouse in a wheelbarrow.

Dust and heat. After resting, the dried bricks are put in a huge kiln. The ovens

are fuelled with wood. The ash is simply dumped in little heaps. I managed to

step on one of the fresh heaps of ash. Blazing sun, 40 degrees Celsius and a

photographer jumping around in a brick factory yard. But after a short rest, I

was ready for the second shift. There were not many gringos working in the

factory. The workers were virtually all Black Brazilians. Some of them worked

straight through both shifts. Tough, very strenuous physical labour…

Salvador, 16. 11 2008

Zoltán Molnár

I got back safely from Rio. A huge metropolis. I was on Mount Corcovado,

whence Christ the Redeemer blesses the city. In the 1980’s Pope John Paul II

also made the pilgrimage to the top of the mountain. I took a little train 700

metres up through a national park amongst tropical trees and flowers. The

mountainside was so steep that from the window all you could see was a wall of

rock on one side and treetops on the other. It was as if the train was

travelling along the tops of the trees. At the top there is a chapel in the base

of the statue. A beautiful bay, the ocean and its perpetual grand waves,

mountains, lakes, rivers. There are luxurious skyscrapers, hotels and banks near

the shore. But on the hillsides are the favelas or slums, where families live on

top of one another in lean-to dwellings. I found a bed in a hostel in a room for

six. The man underneath me snored so loud I couldn’t sleep. His snoring could

have used a bit of accompaniment.

Salvador, 28. 11 2008

Zoltán Molnár

Time flows. There are times when we try to swim against the flow, then we see

we are in the same place or flowing backwards together with time. I met many

people in Rio de Janeiro who cannot swim, people not only born to their fate but

with no chance of getting ahead, studying, perhaps acquiring a diploma, or even

of raising their children. So they are stuck in day to day subsistence, at any

price. Stealing, drugs, prostitution... The poor neighbourhoods or Favel

Barrios, as the Brazilians call them, are on the hillsides. Tin sheds with

corrugated slate roofs, on stilts or at best on cement foundations. Blacks,

Latin-Americans, Brazilians, together in one neighbourhood. A state within a

state. With its own market, church, elementary school, its own football field

and its own laws. It was like looking in on a normal „quiet” South American

morning where children grow up amongst teenagers gathering in gangs and trying

out their guns and various weapons on the street. All this coupled with a

mixture of strange smells: the smell of the sewer, of rubbish or of hashish. I

found no secondary school, library, cultural centre or playground in Rocinho.

There is some foreign aid, but it is no more than a drop in the ocean. There are

more and larger favelas all the time. It seems to me the children have no hope

of a future. All this in a city where the Atlantic ocean washes the sands of the

world’s largest beach, a city that contains not only Sugarloaf Mountain, but a

national park. Light and shade at the same time and in the same place.

Salvador, 25. 11 2008

Zoltán Molnár

I arrived in the rain forest, met the native inhabitants, Indians, people who

live on the water and I met their families. I saw gigantic trees, parrots and a

beautiful Jesuit fortress-church. The first day in the city centre close to Óra

square, I was attacked. I was just changing films when two strong, young

Brazilians forced me with a knife for cutting bamboo to give them my backpack,

which I was holding with both hands. I was forced to let go of it when one of

them made a frightening cut by my stomach; then the other one struck me down. He

hit me in the left eye. I tried to pursue him, but the other one would not let

me. I was not badly injured. They stole my bag with three cameras. All this

happened at 11am, in broad daylight in front of a café and passers-by. I

immediately ran for the police. I found them with great difficulty. They started

looking for the two men with the help of taxi drivers, but without success. They

took me back to the scene. A woman found my films on the ground with my press

card and my notes. I had left my passport, money, documents and bankcard in the

hostel, but unfortunately not my cameras, my watch and my telephone. They took

down a statement of which I was given a copy. The following day I went to all

the used technical and camera shops. My roommate, a broker from Lisbon, helped

me look for a cheap second-hand camera. He helped a lot by questioning local

photographers. I finally bought a very inexpensive camera, which I took with me

to the rain forest. I learned a lot from the episode. It was my fault. I should

have been much more vigilant and careful. I was lucky. I am still alive. I was

the fourth victim at the hostel that week. A Swedish boy was knifed in the arm,

a Frenchman had his watch ripped off…

Salvador, 11. 12 2008

Zoltán Molnár

A real traveller does not pass on his experiences and adventures by showing

only the visible individuality of a place, but shares what he has lived through

within himself. A good photographer puts this across in the composition of his

pictures. The real traveller never arrives in a place which can only be

described as a geographic point of intersection, but proceeds meanwhile on his

inner journey. The good photographer’s pictures do not just show the world

around him and introduce us to people, but talks of himself as well. The real

traveller and the real photographer have their secrets. These are first and

foremost concealed in their personality. Both a good photographer and a real

traveller, Zoltán Molnár has the ability to empathize with and respect other

people, a natural sensitivity, a desire to discover and a pure curiosity without

ulterior motive. This is why his pictures appear to have been brought into being

by the laws of nature in his presence. With their gracious simplicity, the

strength of their lack of complex apparatus, the pictures formulate statements

in simple terms both on the people represented and on their world. The Brazil

Diary photographs and texts tell their stories between black and white, in a

colourful and hectic world. They calm the viewer with their tranquillity and

offer the prospect of an inner journey not to be measured in kilometres.

Gabriella Csizek curator

|

Hungarian House of Photography in Mai Manó House

H-1065 Budapest-Terézváros, Nagymezõ utca 20.

Telephone: 473-2666

Fax: 473-2662

E-mail: maimano@maimano.hu

|

|

|